You Are the Asset: Why Protecting Your Voice and Likeness Is No Longer Optional

By Matthew B. Harrison

TALKERS, VP/Associate Publisher

Harrison Media Law, Senior Partner

Goodphone Communications, Executive Producer

For years, “protect your name and likeness” sounded like lawyer advice in search of a problem. Abstract. Defensive. Easy to ignore. That worked when misuse required effort, intent, and a human decision-maker willing to cross a line.

For years, “protect your name and likeness” sounded like lawyer advice in search of a problem. Abstract. Defensive. Easy to ignore. That worked when misuse required effort, intent, and a human decision-maker willing to cross a line.

AI changed that.

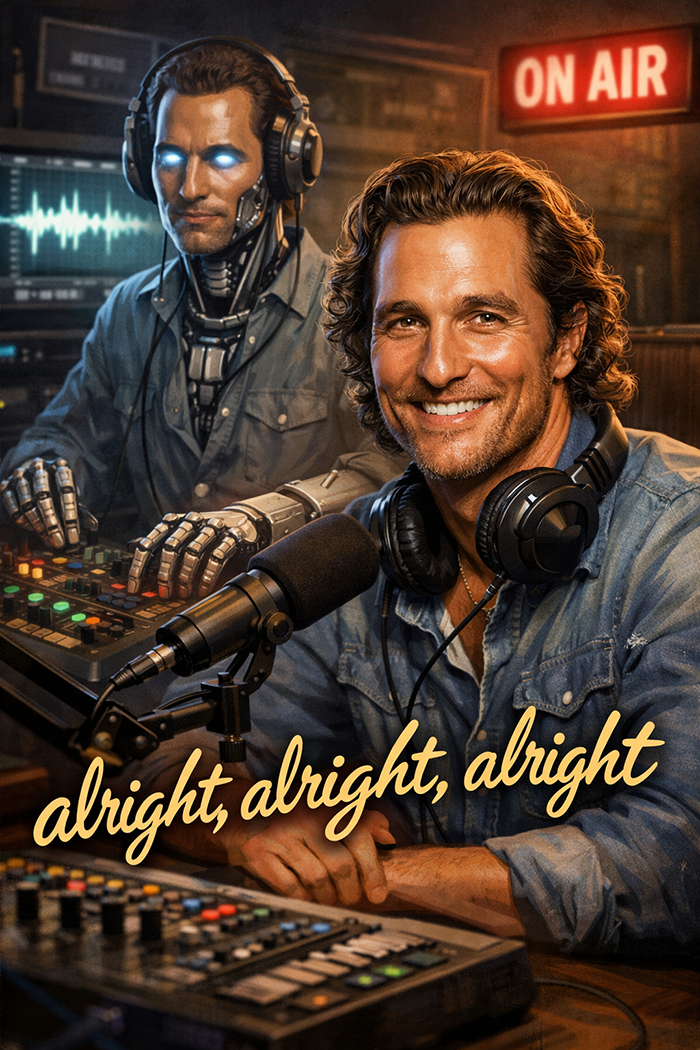

When Matthew McConaughey began trademarking his name and persona-linked phrases (“alright, alright, alright”), it was not celebrity vanity. It was an acknowledgment that identity has become a transferable commodity, whether the person attached to it consents or not.

A voice is no longer just expressive. It is functional. It can be sampled, trained, replicated, and redeployed at scale. Not as a parody. Not as commentary. As a substitute. When a synthetic version of you can narrate ads, read copy, or deliver endorsements you never approved, the injury is not hypothetical. It is economic.

We have already seen this play out. In the past two years, synthetic versions of well-known voices have been used to sell products the real person never endorsed, often through social media ad networks. These were not deep-fake jokes or parody videos. They were commercial voice reads. The pitch was simple: if it sounds credible, it converts. By the time the real speaker objected, the ad had already run, the money had moved, and responsibility had dissolved into a stack of platform disclaimers.

This is where many creators misunderstand trademark law. They think it is about logos and merchandise. It is not. Trademarks protect source identification. Meaning, if the public associates a name, phrase, or expression with you as the origin, that association has legal weight. McConaughey’s filings reflect that reality. Certain phrases signal him instantly. That signaling function has value, and trademark law is designed to prevent identity capture before confusion spreads.

Right of publicity laws still matter. They protect against unauthorized commercial use of name, image, and often voice. But they are largely reactive. Trademarks allow creators to draw boundaries in advance, before identity becomes unmoored from its source.

This is not a celebrity problem. Local radio hosts, podcasters, commentators, and long-form interviewers trade on recognition and trust every day. AI does not care about fame tiers. It cares about recognizable signals.

You do not need to trademark everything. You do need to know what actually signifies you, and decide whether to protect it, because in an AI-driven media economy, failing to define your identity does not preserve flexibility. It invites identity capture.

Matthew B. Harrison is a media and intellectual property attorney who advises radio hosts, content creators, and creative entrepreneurs. He has written extensively on fair use, AI law, and the future of digital rights. Reach him at Matthew@HarrisonMediaLaw.com or read more at TALKERS.com.

In early 2024, voters in New Hampshire got strange robocalls. The voice sounded just like President Joe Biden, telling people not to vote in the primary. But it wasn’t him. It was an AI clone of his voice – sent out to confuse voters.

In early 2024, voters in New Hampshire got strange robocalls. The voice sounded just like President Joe Biden, telling people not to vote in the primary. But it wasn’t him. It was an AI clone of his voice – sent out to confuse voters.